Go back into the blue

The brevity of the rain, sovereignty of the

water as it falls on the trees. When

everything has just turned indigo, the rain

makes the sunrise extend its

grays. It is lovely to watch the world

covered by a cloak that asserts its

continuities, the persistence of a

life in which we will no longer be.

José Emilio Pacheco, “Brevity,” The age of shadows, 2009

In José Emilio Pacheco’s poem, “Concisión,” written toward the end of his life, rain wraps the world in indigo. He describes that blue wash as a cloak, blanketing the grays and shadows that define so much of our mortality. The color is rain and calm, a melancholic sign that the world will go on.

Blue is having something of a moment in the West. Pantone has announced that 2020’s color of the year will be “Classic Blue.” They note that this blue instills calm, confidence, and connection, offering a stable foundation for growth. Poets and essayists have been grappling with the color’s suggestive possibilities for years. Maggie Nelson devoted her book Bluets to her obsession with the color; in her life, it became a constantly appearing and reappearing talisman, a way of understanding loss and grief, a constant companion through transformation. Indeed, the color’s close association with sadness is embedded in language and poetry, embodied most fully in the music of the blues. Perhaps it is less a color than a feeling.

Maya blue, which is at the center of Sandra Monterroso’s investigations, appears in murals and ceramics, in ritual, and in oral tradition for more than a thousand years, long before Western writers arrived at it. The pigment has remarkable endurance, remaining strong and clear for millennia even in harsh climatic conditions. To make this blue, the Maya combined indigo dye (añil) with a clay called palygorskite, known for its curative powers. The pigment and the clay bind together through a firing process with the sacred incense copal. It is, then—even at the molecular level—a healing and resilient color, traditionally connected to the rain god Chaak, and to the element of water.

In Las heridas también pueden teñirse de azul, Monterroso’s works on paper, performance, installation, and textile sculptures are bound by the Maya blue. Her sculpture Vida Azul is a collection of historic threaded pompoms, worn by women in the highlands, woven into their hair. Bearing the life of the wearer, these small, decorative balls of threads carry the energies of their wearer’s experiences. Monterroso has placed them on a nest of twisted añil-stained fabrics; they become crowns to the pendulous twining blue. In the installation Puntos en resistencia azul blue bundles of the same twisted fabric hang from cords attached to the ceiling. Here, they become collections of knots. Resistance is a kind of refusal, a slowing down that doesn’t allow the knots to come undone, a strong reluctance.

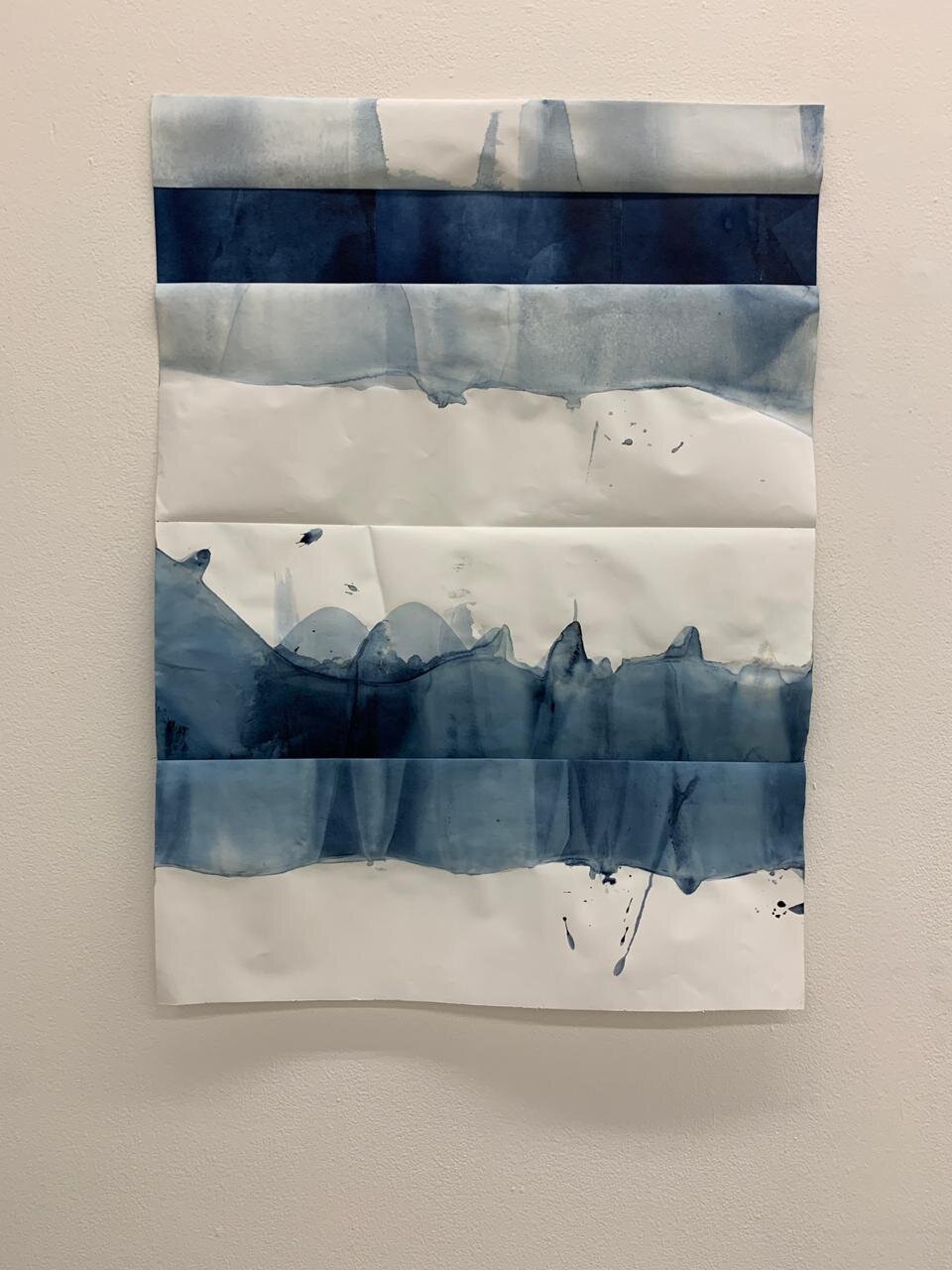

With her recent works on paper, the blue stains the paper in abstract patterns. And yet, the stain refuses any hard edge, making an organic nod to geometry through the watery quality of the color. Water is the color, in its representation, its metaphor, and its very material.

The centerpiece of the exhibition is a performance-installation the artist has titled El agua se volvió oro, el río se volvió oro, el oro se volvió azul, which she performed earlier this year at Ex Teresa Arte Actual in Mexico City. Laying at the foot of a long, blue textile that runs down the wall and to the floor, the artist makes an invocation to the spirit of water, calling it back to the river. The textile, constructed of güipiles from the artist’s home state of Alta Verapaz, flows in gentle rivulets, covering the artist’s body until only her head appears. She describes the extractive industries that are destroying Guatemala’s waterways and traditional methods of caring for them as wounds: “the rivers, the lakes, even the oceans, are wounded,” she writes. It is significant that she turns to weavers—to a tradition connected to collaborations among women—to invoke the river. Water and healing are the realms of the feminine, sites of female strength, wisdom, and magic.

Blue is intangible and remote, Rebecca Solnit writes. If we can imagine touching blue, we can imagine touching distance: recall that in drawing and painting, western perspectival systems use blue to signify the far-away. It is a color that describes where you cannot go, where you will never be, where you imagine yourself, and where you want to be. It is not only a color, but a space, just out of reach. That is to say, blue also has to do with the act of wanting, at the scale of the body.

Blue might be the past. It might bear sadness, might offer healing. What Monterroso proposes is that blue is a color of pain, the color with which hurt stains itself. Embedded with ancestral and sacred knowledge, it is also a color with history, resilience, and power, a color that fills the holes of hurt within us.

“During the blue nights you think the end of day will never come... Blue nights are the opposite of the dying of the brightness, but they are also its warning,” writes Joan Didion after the death of her daughter. “Fade as the blue nights fade, go as the brightness goes. Go back into the blue.”

—Laura August

Houston, TX

December 2019